Delayed umbilical cord clamping has a variety of benefits for newborns and is the current standard of care at the time of delivery.

Does your cord blood collection agency adhere to these medical and ethical standards? Read on to learn more.

In the past 10 years, the cell therapy industry has developed drugs that treat inherited blindness, have cured certain forms of blood cancer, and have sent diseases such as HIV into remission. These milestones have encouraged large amounts of investment in and development of the industry, spawning biotechnology companies and accelerating traditional, large pharmaceutical companies moving into the field.

Cell therapies are made through a manufacturing process that relies on raw materials that are procured from industry suppliers. Umbilical cord blood is one such raw material source that has grown in popularity because it is an easily accessible source for hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSCs) and immune cells, which can be used in transplantation and in the development of cell-based immunotherapies (read more here). Researchers rely on the procurement of cord blood for the advancement of their studies and often require large amounts of this potent source material. There is a direct, proportional relationship between the volume of blood in a cord blood unit (CBU) and the number of HSCs and immune cells that can be isolated from the blood. Thus, the natural inclination is to collect as much cord blood volume as possible from the cord tissue. This, however, poses a potential ethical issue for the physician and the cord blood collection agency.

The collector of cord blood – usually an OB/GYN – needs to strike a balance between how much blood flows to the newborn versus how much is collected. The American College of Gynecology and Obstetrics (ACOG) provides guidance on how to strike this balance through a process called “delayed umbilical cord clamping.”1 ACOG recommends a delay in umbilical cord clamping in vigorous term and preterm infants of at least 30–60 seconds after birth.1 The volume of blood collected is determined by two main variables: (i) the donor’s profile (e.g. age, weight, etc.), which determines the total amount of cord blood in the umbilical cord, and (ii) the method of collection, which determines how much cord blood flows to the newborn baby versus into a collection bag.2

Full term infant blood volume distribution is about 1/3 in the placenta and 2/3 in the fetus. While initial breaths taken by the newborn allow for 90% of blood in the placenta/cord tissue to transfer to the newborn, delayed clamping of the cord by at least 30 seconds, allowing for more blood return to the newborn, has been shown to improve neonatal outcomes.2-4 This practice allows extra iron, antioxidants, stem cells, and antibodies to flow from the placenta into the baby. In 15 clinical trials including 3,911 women and their babies, early cord clamping – defined as clamping less than 1 minute after birth – resulted in significantly lower concentration of hemoglobin at birth, as well as increased likelihood of iron deficiency at 3-6 months of age, compared to outcomes with delayed cord clamping (DCC) – defined as clamping more than 1 minute after birth or when cord pulsation stops.1,4,5 Although jaundice requiring phototherapy was slightly increased in infants with delayed cord clamping, the effectiveness of jaundice management regimens has led the medical community to determine that the benefits of DCC outweigh the risks.3-5

Earlier studies focused on preterm or intra-uterine growth restriction babies concluded that DCC resulted in increased stem cell transfusion, lower incidence of anemia requiring transfusion, and significantly less intraventricular hemorrhage and necrotizing enterocolitis (a serious disease that affects the intestines) in newborns.3,5 There was no significant difference in the need for phototherapy treatment for jaundice with or without DCC. When it comes to maternal outcomes, studies conclude that DCC is not associated with postpartum hemorrhage or blood loss at delivery. In addition, there is no increased need for blood transfusion or low postpartum hemoglobin level. 3-5

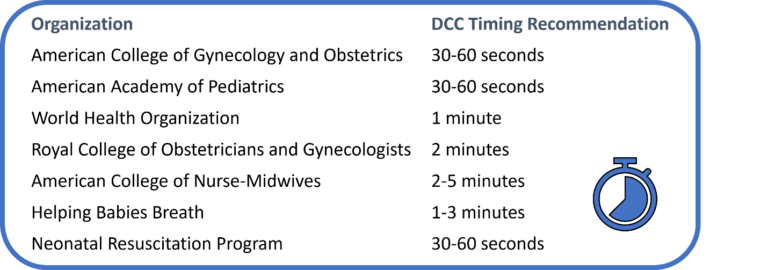

Given the obvious benefits to the newborn and no significant risk for the mother, many professional organizations are now in agreement when it comes to DCC recommendations (see chart below). The recommended times of DCC vary depending on gestational age, position of the newborn in relation to the placenta, signs of vigor, respiratory function of the newborn at the time of birth, and risk for maternal hemorrhage. Physicians must use their judgment to determine the duration of DCC based on these metrics.

As a result of DCC, cord blood collection volumes can vary greatly, from as little as 30mL to 100mL.3 Variation is due to a number of factors including newborn age, weight of the infant, placenta size, umbilical cord length, and/or timing of DCC. However, the average cord blood unit volume has decreased significantly following the implementation of DCC guidelines, and CBUs over 100 mL are now very rare if physicians adhere to these guidelines during birth. Thus, DCC results in significantly lower cord blood volume and cell count, which in turn leads to cord blood units which may be unsuitable for transplantation or the isolation of cells of interest. This, in turn, may lead some birth tissue collection organizations to encourage non-adherence to ACOG and other guidelines for DCC.

OrganaBio collects birth tissues (including cord blood) through its wholly owned, FDA-registered subsidiary, GaiaGift. Tissues are collected from consented, non-compensated donors, under IRB approved protocols, to provide researchers with high quality cellular raw materials for the advancement of cutting-edge cell therapies. The OrganaBio team works closely with physicians to educate medical professionals and donors about perinatal tissue donation and the ethical and medical implications of the collection process. OrganaBio has an unwavering commitment to the ethical collection of tissues, putting the health and well-being of moms and newborns at the forefront of operations, and OrganaBio physicians strictly adhere to DCC guidelines, despite lower cord blood volume yields.

It is imperative upon the scientific community to find the balance between benefits to the infant and the volume of cord blood collection. Ultimately, a collection procedure that does not strictly adhere to medical guidelines may put an entire cell therapy program at risk. As such, OrganaBio works with our scientific partners to explore next-generation tools and technologies to optimize cell yield from cord blood units collected to meet the highest medical and ethical standards.

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric Practice. Delayed Umbilical Cord Clamping After Birth: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 814. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Dec;136(6):e100-e106

- Bruckner M, Katheria AC, Schmölzer GM. Delayed cord clamping in healthy term infants: More harm or good? Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021 Apr;26(2):101221.

- DuPont, T. L., & Ohls, R. K. (2018). Placental Transfusion: Current Practices and Future Directions. NeoReviews, 19(1), e1–e10.

- Gomersall J, Berber S, Middleton P, et al. Umbilical Cord Management at Term and Late Preterm Birth: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2021;147(3):e202001540

- Surak A, Elsayed Y. Delayed cord clamping: Time for physiologic implementation. J Neonatal Perinatal Med. 2022;15(1):19-27.